In the 2012 biography Satan Is Real: The Ballad of the Louvin Brothers, famed singer- songwriter Kris Kristofferson states “the legendary Louvin Brothers’ hauntingly beautiful Appalachian blood harmony is truly one of the treasures of American music”. In order to gain a deeper understanding of the Louvins’ songwriting and themes, it is helpful to first examine their lives and culture. Charlie and Ira Loudermilk were born in Henagar, Alabama within the southern region of Appalachia as designated by the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC). The brothers were born to Colonel Monero Allen and Georgianne (née Wooten) Loudermilk, a farmer and preacher’s daughter respectively. The Loudermilks were cotton farmers, and each of the family’s six children learned to work in the fields from an early age. Charlie Louvin has reflected in several interviews and books that his father drove his siblings quite hard, giving examples of how Loudermilk would give his son or daughter that picked the most cotton that day a five-dollar bill, and then stating that if they did not meet that same quota the next day, they would be beaten. Colonel Loudermilk was known for his fiery temper from his own drunken and abusive upbringing, a quality that would later be passed on to his son, Ira, and whose character came to be alluded to in several of the brothers’ later songs.

Charlie and Ira began learning old English ballads from their mother, and they crafted their harmonies to fit around the traditional songs. According to scholar Thomas Wilmeth, the Loudermilk family was also involved in the Sacred Harp singing style, a derivative of the shape- note form of musical transmission that was particularly popular in the Sand Mountain, Alabama area in the early 1900s. Author Charles Reagan Wilson refers to this form of singing as an art that played a key role in defining the region’s “spirituality,” and Charlie and Ira certainly exemplified this mindset in their own music.

The boys had no formal musical training, and thus they improvised a style of harmony singing that borrowed techniques from the shape-note singing meetings while not relying on the tenets of standard harmony, instead crossing and meeting vocal lines in a fresh and captivating way. As the brothers began to hone their skills, their father took notice, and he drew his bashful sons out with impromptu performances at the local Sacred Harp singings and community gatherings—a tactic which made the duo more comfortable performing for audiences. Charlie and Ira eagerly listened to brother duets such as the Blue Sky Boys, the Monroe Brothers, and the Delmore Brothers, as well as Grand Ole Opry stars like Roy Acuff on the radio. While the brothers felt that they were vocally able to compete with the leading brother duets of the day, they lacked instrumental skills and decided to learn guitar and mandolin in order to make themselves more marketable and successful. They also changed their name from Loudermilk to “Louvin” (an amalgamation of names developed while brainstorming one night) to further this goal.

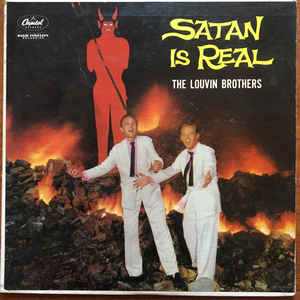

Charlie and Ira’s ultimate ambition was to play the Grand Ole Opry stage, which contrasted vividly with their father’s goal to see the boys performing songs of faith for their small rural community. In order to make ends meet, the brothers set aside the puritanical values that they so frequently sang about to perform at local carnivals and pool halls, and eventually they gained some recognition winning a Chattanooga, Tennessee, radio competition that offered a weekly radio show as a first-place prize. Soon afterward, Smilin’ Eddie Hill, the station manager at WMPS in Memphis, offered the Louvins a job on yet another country music radio station, billing them as “the world’s best duet”. The duo spent the next few years recording sides for Apollo, MGM, Acuff-Rose, and Decca, while performing on various local barn dances. Their arguably biggest break came when they signed a contract with Ken Nelson and Capitol Records in 1952 to record gospel material with one of the industry’s leading guitar sideman, Chet Atkins. In 1955, Charlie and Ira Louvin played the Grand Ole Opry stage after being introduced by their boyhood hero, Roy Acuff. Their career skyrocketed, and musicians such as Johnny Cash and Elvis Presley became fans of the duo’s distinctive harmonic arrangements and emotive songwriting.

Charlie and Ira Louvin’s striking vocal blend resulted from a combination of influences found within their cultural traditions. Henagar, Alabama, is centered within a hotbed of Appalachian musical customs, and the brothers readily accredited the formation of their vocal style to their family’s involvement in Sacred Harp singing, coupled with their mother’s love of ancient Scots-Irish ballads. An examination of this community-driven music explains the impact that Sacred Harp shape-note singing had on the Louvin Brothers and also reveals its importance to Appalachia.Sacred Harp singing is a derivative of the shape-note singing mode of transference and construction of melodies. Based upon the concept that notes printed in different shapes are easier for beginning singers to read than theory-based standard notation, shape-note singing utilizes different syllables and pairs them with distinctively formed notes to guide singers to associate them with tonal differences. This formatting of shaped notes, while seemingly complicated, was in fact an effort to facilitate faster learning from unskilled singers, which led to the gradual implementation of the teaching technique in America during the 1700s. By the 1800s, the music was a valuable social art form, and collections of songs in tunebooks such as Ananias Davidson’s 1816 volume Kentucky Harmony, Andrew Law’s book entitled The Musical Primer, and perhaps the most well-known and beloved out of all of the songbooks—The Sacred Harp—had become treasured volumes in the homes of many churchgoers. However, The Sacred Harp remained unique in that it not only spawned a specific style of singing (which incorporated four-note transcriptions, shunned instrumentation, and utilized a powerful full-voice singing style), but also became one of the most enduring vocal forms in the Baptist congregations found in lower Appalachian states such as Alabama. As Ira Louvin learned to harmonize with Charlie, he chose to simulate the multiple harmony parts in the Sacred Harp tradition with his unconventional alternation between the tenor and baritone harmony parts. This, combined with the powerful full-voice projection of the lyrics also drawn from their shape-note singing roots, created the distinct sound that audiences could readily identify and ensured that they were distinguishable from many of their contemporaries.

While Charlie and Ira Louvin were certainly influenced musically by the Sacred Harp songs that they were exposed to in their youth, they also heard thematic content from these songs that they drew upon for the rest of their songwriting career. The classic tunebook served as a collection of many canonical shape-note hymns, and the topics that they covered spanned from the joyful celebration of the Christian who has gained salvation to the guilt-ridden backslider lost in sin. From the over 500 pages in The Sacred Harp, three hymns in particular typify the primary elements of this style of shape-note singing, and through lyrical analysis, show a progression through the Christian life that the Louvin Brothers would have been quite familiar with.

“Idumea” is one of the most recognizable pieces from the shape-note singing tradition, thanks to its inclusion in both the Southern Harmony and Missouri Harmony tunebooks before The Sacred Harp was published. It was also featured in the award-winning film Cold Mountain in 2003, which revived an interest in shape-note singing through its soundtrack. Its thematic content varies noticeably from the previous two hymns in that its lyrics do not contain positive statements of belief, but rather existential questioning of the human condition and fate. The first verse begins with the line “And am I born to die?” effectively opening the song with the haunting question that sets the tone for the rest of the piece. The speaker considers the possibility of life after death and shows uncertainty in the “world unknown” that they will eventually join. The song portrays the two possibilities that face mortals—either the “woe” and damnation that comes from living according to the world, or the “eternal happiness” and salvation that reward a faithful Christian. However, “Idumea” portrays a speaker who seems initially unsure of whether their decision to follow Christ will ensure that they go to heaven, before the final verse indicates their regained faith that God will raise them with all believers on the Judgement Day to see “the Judge with glory crowned” at the “trumpet sound”. The contrast from the questioning beginning of the song to the exclamatory final lines indicates a theological and mental transformation, and the speaker’s conviction of God’s power and justice after death ends the song victoriously.

A differing depiction of God is found in the hymn “America.” Instead of the mighty all- powerful God from “Idumea,” he is portrayed as a kind and gracious heavenly father. The speaker frames the song in the first line as a song of “praise,” and proceeds to introduce the primary qualities that they see in God within each of the three verses. While the first stanza establishes God as merciful and slow to anger, the next praises his abundant and seemingly inconceivable grace, and the final introduces the theme of God as loving forgiver. However, the speaker takes care to acknowledge that while they use the image of God as a gentle and forgiving father, he does rely upon his power and might to “subdue” his children’s sins. This word choice alludes to a concept of God’s power effectively squelching the desire to sin and simply removing temptation rather than relying on the person’s individual conscious decision to resist the temptation, providing a theological counterpoint to personal responsibility. This description also portrays God as the mediator between his children and their sins, rather

than Christ, despite the fact that Jesus traditionally acts in this role in New Testament scriptures such as 1 Timothy 2:5, which states “For there is one God, and one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus” (King James Version). Nevertheless, the two sides of God as benevolent father yet powerful protector prove to be a theme that appears quite frequently within sacred lyrics, and likewise appear in several hymns within The Sacred Harp tunebook. The song ends with one last fatherly reference in the form of a biblical reference to Psalm 103:12, stating that God will lovingly discard his children’s guilt as “far as the east is from the west”. “America” gives singers and listeners hope that their sins will be overcome and that their heavenly father will gently guide them through life in his great love.

“Primrose Hill” shows the certainty of the individual who believes in God’s salvation. The song begins with the speaker stating that they will no longer fear or despair over their life when they “read” their “title” (or deed) “to mansions in the skies,” or when they know that they have received God’s salvation. The persona continues their fearless assertions, claiming that they could even face Satan’s wrath with a smile under the knowledge of God’s protection. The speaker calls God “my all” and expresses implicit confidence in him despite the “storms of sorrow” and “wave[s] of trouble” that may face them. The language of the song sets up the vast contrast between the two major locations in the lyrics—the imagery of the serene heaven uses such words as “rest,” “peaceful,” and “home,” while the opposing, warlike, hellish world is depicted alternatively with “fier [sic] darts,” “frowning,” and “rage”. As well, great care is taken in the lyrics to consistently refer to God and his kingdom of the heavenly skies, while similarly pairing references to Satan and the Earth as the devil’s domain. However, the peace that “Primrose Hill” presents as an alternative to this earthly disorder can be enjoyed only through denying the world and obtaining a “title” to the heavenly mansion in the first line or becoming a Christian. The song’s structure shows the confidence of the speaker in their salvation through the series of certain declarations (unlike “Idumea,” which instead questions the troubling fate of humankind) and the narrator maintains a positive outlook on their future throughout. While the hymn ultimately evidences that Christianity does not prevent the worldly suffering that does face believers, “Primrose Hill” also presents the perspective that faith in heavenly protection both in this life and the next makes these trials endurable.

These three hymns suggest a progression of events within the Christian life. In the first hymn, “Idumea,” the narrator raises questions about mortality and the ultimate fate of their soul before regaining confidence in God’s ability to raise them from death on the judgement day. This faith therefore gives them the reassurance of the persona in “America,” who maintains that God provides them with the love, grace, and mercy that they need to face their daily existence on earth. Finally, “Primrose Hill” discusses the life after death that the speaker believes awaits them and comforts the believer through its depictions of the peace that will await them if they maintain their faith. Tracing the life of a believer through these hymns provides insight into the beliefs of the Louvins’ church community and the later formation of the brothers’ sacred compositions.

While Charlie and Ira Louvin were hugely influenced by their father’s involvement in the local Sacred Harp singings, the credit for their musical development must also be shared with their mother Georgianna’s enthusiasm for traditional British balladry. Georgianna’s father was a Baptist preacher within the northeast Alabama community of Henagar, and in keeping with the family’s English heritage, Charlie and Ira’s mother taught them the same songs that she sang as a girl. The young Louvins learned multiple selections which they would later implement into their repertoire, such as “Mary of the Wild Moor,” which proved to be a song that would stay with the brothers throughout their career. The importance of songs like this particular example reveal just how crucial the musical traditions from the Scots-Irish were to Appalachian communities like the Louvins’.

“Mary of the Wild Moor” is a song which was originally printed as a British “broadside ballad” in the early 1800s. The lyrics tell the melancholy tale of a needy young woman estranged from her family. While she is clearly more concerned for the welfare of her child than herself, Mary is also close to death, and when she arrives at her parents’ house, crying over the noise of the wind for her father to save her, he does not hear her voice. In the sequential verses, the unfortunate girl’s father finds her lying dead near the door, with her child just alive. Both Mary’s father and her child pass away from their loss, and the song ends with a somber reminder of the girl who was once a carefree and beautiful bride and her tragic end which haunts the village.

This particular ballad is constructed in standard ballad fashion, which relies on sequential verses to depict an incident with an alternating chorus to break up the narrative. However, the Louvins chose to insert two instrumental breaks after the third and sixth verses, interstitial interludes that act to provide a pause for reflection to the listener similar to the function of line breaks in poetry. To this point, it is also quite evident to observe that several components of the ballad allude to literary conventions. The doleful subject matter follows the pattern of many songs and pieces of literature also situated within the Romantic period of the late-1700s to mid- 1800s, which often appealed to an audience’s imagination through the liberal use of pathos. Themes such as nature, remembrance of the past, and human reason and consciousness were all found in pieces of high literature and poetry from this time period, and the masses were being entertained with such popular literature as the penny dreadful, designed to sensationalize through melodrama. These theatrical motifs accordingly alluded to the Gothic themes which had been in existence since the mid-1700s, and echoed tropes of contemporary literature such as isolation, darkness, horror, and drama to create a sense of dread in audiences. The ballad’s setting of the shadowy, dreary, and windblown moor and eerily howling watchdog, combined with the tragic death of the protagonist and the subsequent ruination of the family house, all draw heavily upon this theme of the Gothic.

The song’s lyrics show several disturbing plot twists which elicit the listener’s compassion towards the unfortunate family. Firstly, although the song’s conclusion states that Mary was “once the gay village bride,” no mention is made of her husband throughout the piece. Mary’s mother is similarly noticeably absent from the ballad, placing the responsibility squarely on the father as the nearest relation to help the girl. However, while the narrative is careful to portray him as a responsible and loving father, the old man unintentionally lets his family down three times; once, as he fails to hear his daughter calling to him, twice, in that he unwittingly agrees to let his daughter marry a man who does not provide for her wellbeing, and the third and final time as he leaves Mary’s child with no one to take care of it after its mother’s death. This involuntary abandonment becomes even crueler considering that there are no indications of previous ill will towards Mary from her family, and there appears to be no ostracism from her kin. The pathetic conclusion is that Mary’s story becomes a folktale to the villagers, and the protagonist dies alone and deserted by the key male figures in her life who could have saved her from her dismal end. The ballad ends with a narrative reminder of how much Mary’s miserable death contrasted from her happy youth, and both the heroine’s search for shelter and charity and her father’s remorse and grief elicit compassion from the listener.

The Louvins were certainly no stranger to the emotional impact of ballads such as “Mary of the Wild Moor,” as they recorded similarly somber subject matter countless times, and they eventually recorded the song that had remained with them for so many years in 1956 with the release of their album Tragic Songs of Life, which acted as a compilation of the duo’s most heart- wrenching selections. The Louvins present “Mary of the Wild Moor” plainly, with a relatively sparse arrangement of acoustic and electric guitar, mandolin, and a snare drum, instead choosing to showcase their splendid harmonies. As the listener studies Charlie’s steady, pure melody line and Ira’s Sacred Harp-inspired harmony line which crosses from tenor, to unison for effect, and finally to baritone almost effortlessly, it is clear that both the recording’s subject matter and the music itself exemplify the components of what can be called the distinctive Louvin Brothers sound.